Traditional Japanese textiles, known as "Ori-mono," have developed across various regions alongside Japan's history. From Hokkaido to Okinawa, different types of textiles are still woven today, reflecting the unique materials and techniques of each area. Let’s delve into the features, history, techniques, and varieties of Japanese textiles to explore this fascinating traditional craft!

👉 Buy Traditional "Ori-mono" (Yahoo! Shopping)

* If you purchase or make a reservation for the products introduced in the article, a part of the sales may be returned to FUN! JAPAN..

Characteristics of Japanese Textiles

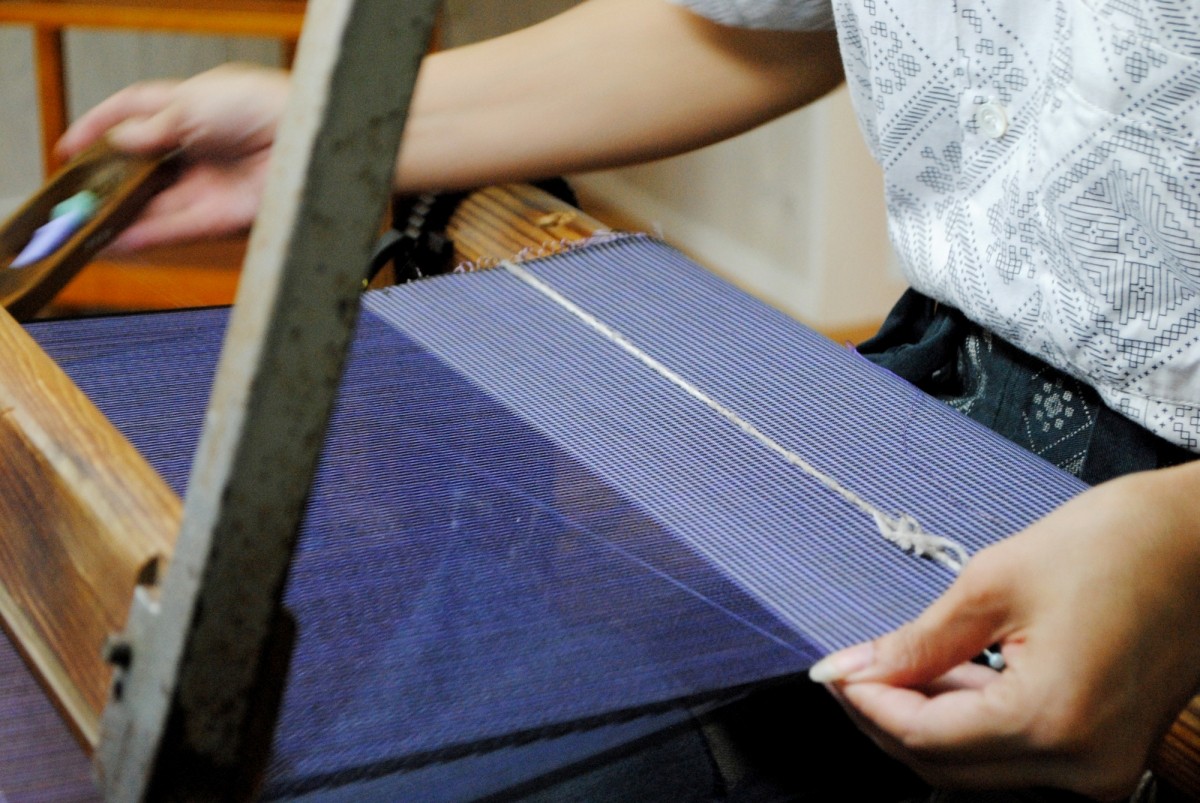

Japanese textiles are made by weaving dyed threads together on a loom, intertwining vertical warp threads (tate-ito) with horizontal weft threads (yoko-ito) to create fabric. Because the threads are dyed before weaving, the fabric is also referred to as "yarn-dyed." One distinctive feature of Japanese textiles is the ability to create a wide variety of patterns and textures through different dyeing, weaving, and twisting methods. Additionally, the climate and natural features of each region contribute to producing textiles with unique, local characteristics.

The History of Japanese Textiles

The history of Japanese textiles dates back to the Jomon period. This is evident from weaving tools unearthed at sites such as the Suzume-no-i archaeological site in Fukuoka Prefecture, proving that weaving was already practiced during this time. However, the textiles of that era were simple, made from plant fibers like hemp or ramie.

During the Nara period, Japan was influenced by ancient Chinese culture, leading to the spread of high-quality silk textiles among the upper class. In the Heian period, weaving techniques further advanced, resulting in uniquely Japanese patterns worn by members of the imperial family and aristocracy.

By the Edo period, sericulture (the production of silkworm cocoons) was encouraged, enabling Japan to produce high-quality silk textiles domestically. Techniques and looms from Kyoto’s Nishijin weaving spread across the country, establishing silk textile production areas in regions such as Chubu, Kanto, Hokuriku, and southern Tohoku. From the modern era onward, industrialization led to mass production, but traditional hand-weaving techniques have been preserved, keeping this heritage alive.

*Late Jomon period: approximately 2000–1000 BCE, Muromachi period: 1336–1568, Heian period: 794–1180, Edo period: 1603–1868.

Basic Weaving Techniques in Japanese Textiles

Japanese textiles are primarily categorized into three basic weaving techniques, with most textiles woven using these methods. Recently, a fourth method called "Mojiri-ori" has also been included as a fundamental technique.

Hira-ori (Plain Weave)

Hira-ori is the most basic weaving technique where the warp threads and weft threads intersect alternately, one by one. This method creates numerous crossing points, making the fabric durable and resistant to wear. It produces relatively thin fabrics, but by varying the quality, thickness, and twist of the threads, it can achieve different textures.

Aya-ori (Twill Weave)

Aya-ori involves passing one weft thread under two or three warp threads, creating diagonal crossing patterns. Due to this characteristic, it is also known as "Shamon-ori" (diagonal weave). Compared to plain weave, twill weave has fewer crossing points, making it slightly less wear-resistant but suitable for creating thicker fabrics. It is also flexible and less prone to wrinkling.

Shusu-ori (Satin Weave)

Shusu-ori is a weaving technique where the crossing points are spaced apart, a method referred to as "flying." This arrangement results in only the warp or weft threads appearing on the fabric's surface, giving it a glossy finish. With fewer crossing points than twill weave, it is less resistant to wear but has a smooth texture. A well-known fabric made using this technique is satin.

Mojiri-ori (Leno Weave)

Mojiri-ori, also known as "Karami-ori," involves intertwining warp threads between the weft threads to create a net-like fabric with open spaces. This lightweight, breathable weave is used to produce summer fabrics like Sha, Ro, and Ra, which are collectively referred to as "Usumono" (light fabrics).

Varied Weaving Techniques in Japan

Japanese weaving techniques have evolved by adapting these basic methods, altering thread dyeing, thickness, and other factors. Here are some notable examples:

Tsumugi

Tsumugi is a silk fabric woven with unevenly spun "tsumugi threads," which have irregularities such as thick spots and slubs. This gives the fabric a rustic texture. Historically, tsumugi was often used for everyday wear, with each region producing textiles suited to its unique climate and environment. Today, tsumugi textiles are preserved as local specialties across Japan.

Kasuri (Ikat)

Kasuri is a fabric created by weaving threads dyed in patterns to produce designs that appear blurred. The dyeing process involves techniques like "Kukuri-zome" (tie-dyeing), "Itajime-zome" (board clamp dyeing), and "Ori-jime" (woven resist). These dyed threads form distinctive blurred patterns when woven.

Chirimen

Chirimen is a silk fabric woven with weft threads that are tightly twisted, creating fine wrinkles (shibo) on the surface. These wrinkles make the fabric resistant to creasing. Recently, chirimen has also been made with synthetic fibers in addition to silk.

Chijimi-ori

Chijimi-ori is a wrinkled fabric made primarily from cotton or hemp. It uses tightly twisted weft threads and undergoes a process of hand-kneading in warm water to create wrinkles. The fabric does not stick to the skin, making it ideal for summer kimonos.

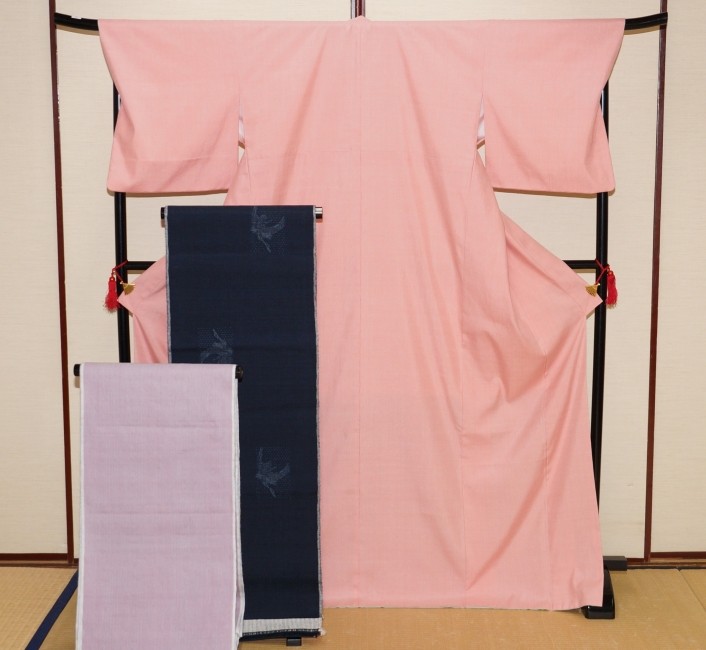

Representative Textile Production Areas and Their Characteristics

Japan's diverse climate and geography, with distinct seasons, have given rise to various textiles suited to each region's environment. There are 38 textile types designated as "Traditional Craft Products" by the Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry. Each production area has its unique characteristics, and these textiles are used in kimonos, traditional accessories, as well as Western clothing and jewelry.

Nishijin-ori (Kyoto)

Nishijin-ori refers to silk fabrics produced in the Nishijin district of Kyoto, named after the western army's headquarters during the Onin War (1467–1477) in the Muromachi period. This textile includes various weaving techniques, with 12 of them, such as "Tsuzure-ori" (tapestry weave) and "Tate-nishiki" (warp brocade), designated as Traditional Craft Products.

A particularly captivating type of Nishijin-ori is "Nishijin Kinran," which combines gold and silver threads, often wrapped in foil, with designated techniques to produce elaborate fabrics. From these luxurious designs to everyday tsumugi and kasuri, Nishijin-ori offers a wide variety of textiles.

Honba Oshima Tsumugi (Kagoshima)

Honba Oshima Tsumugi originates from the Amami region in southern Kagoshima Prefecture. This 100% silk fabric is known for its elegant colors and luster. Unlike typical tsumugi, which uses uneven threads, Honba Oshima Tsumugi is made with raw silk.

The production process involves more than 30 steps and takes six months to a year to complete. Its most notable feature is the intricate patterns created by meticulously weaving pre-dyed threads with perfect alignment. A representative design is the Tatsugo pattern, depicting a palm frond and a venomous habu snake native to Amami. Honba Oshima Tsumugi is also lightweight, smooth, wrinkle-resistant, and incredibly durable, lasting 150–200 years.

Yuki Tsumugi (Ibaraki and Tochigi)

Yuki Tsumugi is a silk fabric made with tsumugi threads produced in the Kinu River basin spanning Ibaraki and Tochigi prefectures. With over 40 mostly manual production steps, it is one of Japan's most precious textiles. The processes of spinning yarn, tying threads for Kasuri dyeing, and weaving on a traditional ground loom have been designated as National Important Intangible Cultural Properties. In 2010, Yuki Tsumugi was registered as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Key features include its lightweight texture, excellent insulation, and soft touch. The signature pattern is the hexagonal tortoiseshell design, or "Kikkou" motif. A single bolt of fabric (approximately 40 cm wide) contains 80 to 200 tortoiseshell patterns. The more intricate the design, the greater the skill required to craft it.

Kurume Kasuri (Fukuoka)

Kurume Kasuri is a cotton fabric traditionally woven in and around Kurume City, Fukuoka Prefecture. Designated as a National Important Intangible Cultural Property, it undergoes around 30 production steps, requiring several months to complete.

The defining characteristics of Kurume Kasuri are its blurred or smudged patterns, a result of its unique dyeing process, and the natural qualities of cotton, which keeps wearers cool in summer and warm in winter. The fabric becomes softer and more comfortable with each wear and is durable enough to be washed at home.

The basic design, known as "Yagasuri," features a feathered arrow pattern achieved by offsetting warp threads dyed in shades of blue and white. Modern advances in technology have also made it possible to create various other designs.

Ojiya Chijimi (Niigata)

Ojiya Chijimi is a hemp-based textile woven in and around Ojiya City, Niigata Prefecture. It evolved from the Echigo Jofu fabric, which has been crafted for over a thousand years. Both Ojiya Chijimi and Echigo Jofu are recognized as National Important Intangible Cultural Properties and were added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2009.

This textile's hallmark is its distinctive crepe-like texture ("shibo") and the breathable qualities of hemp, making it an ideal choice for summer wear. After weaving, the fabric is often exposed to snow to naturally bleach it, resulting in its brilliant colors and patterns.

Comments