Are you familiar with lacquerware, one of Japan's most renowned traditional crafts, referred to as "JAPAN" in English? Lacquerware involves coating wooden utensils with lacquer, the sap of lacquer trees, to create elegant, high-gloss pieces with a luxurious feel. This article explores the unique charm of lacquerware, often described as "living" tableware because its luster and clarity deepen the more you use it. Let’s uncover the allure of Japanese lacquerware.

* Please note that by purchasing or booking any of the products featured in this article, a portion of the sales may go to FUN! JAPAN.

🌸Book your Makie lacquerware experience here.

Features of Japanese Lacquerware

Lacquerware is crafted by coating wooden utensils with layers of lacquer, a sap from lacquer trees, resulting in a distinctive sheen and luxurious appearance. Known as "JAPAN" in English, it is one of Japan's most iconic traditional crafts. Beyond its aesthetic appeal, lacquer has powerful preservative and antibacterial properties and enhances durability. This makes lacquerware not only beautiful but also lightweight and sturdy, characteristics highly valued in daily use.

Lacquerware production sites are scattered across Japan, and each region has its own unique styles, shapes, lacquer application techniques, and decorations. These differences stem from factors like the types of trees grown locally and the preferences of local artisans and regional rulers who supported lacquerware production. As a result, even neighboring production areas can have completely distinct lacquerware styles that have been passed down through generations.

The Lacquerware-Making Process

Lacquerware ranges from affordable pieces to high-end creations, and the difference lies in the craftsmanship involved in its production. The creation of lacquerware typically involves four main stages. Each of these stages consists of multiple detailed steps, but these four primary processes significantly shape the final product's features. Understanding these stages may help you distinguish between authentic lacquerware and imitations.

Kiji-Making (Wood Base)

"Kiji" refers to the bare wooden base of lacquerware before any lacquer is applied. The artisans who craft this base are called kijishi. Not all types of wood are suitable for kiji-making. In Japan, finely grained, smooth woods like cedar, cypress, pine, zelkova, and horse chestnut—mainly softwoods—have been traditionally used for their ideal qualities.

Undercoating

Undercoating strengthens the wood before lacquer is applied in earnest, and the methods vary depending on the region. For instance, cracks in the kiji may be filled with a mixture of raw lacquer (ki-urushi) and wood powder. In other cases, powdered materials like local soil or volcanic ash are burned and mixed with raw lacquer before application. The strength of lacquerware heavily depends on this stage, so it’s recommended to check whether proper undercoating techniques have been applied when purchasing lacquerware.

Lacquering

Lacquering is the main step in the production of lacquerware. This process features a variety of techniques, many of which are unique to specific regions, making it the defining factor that distinguishes different production areas. Typically, there are three stages: undercoating, middle coating, and top coating. If no additional decorations are applied, the process often ends with these steps. For added shine or a smoother texture, finishing techniques like roi-shiage (polishing) or hana-nuri (glossy finishing) may be performed afterward.

Decoration

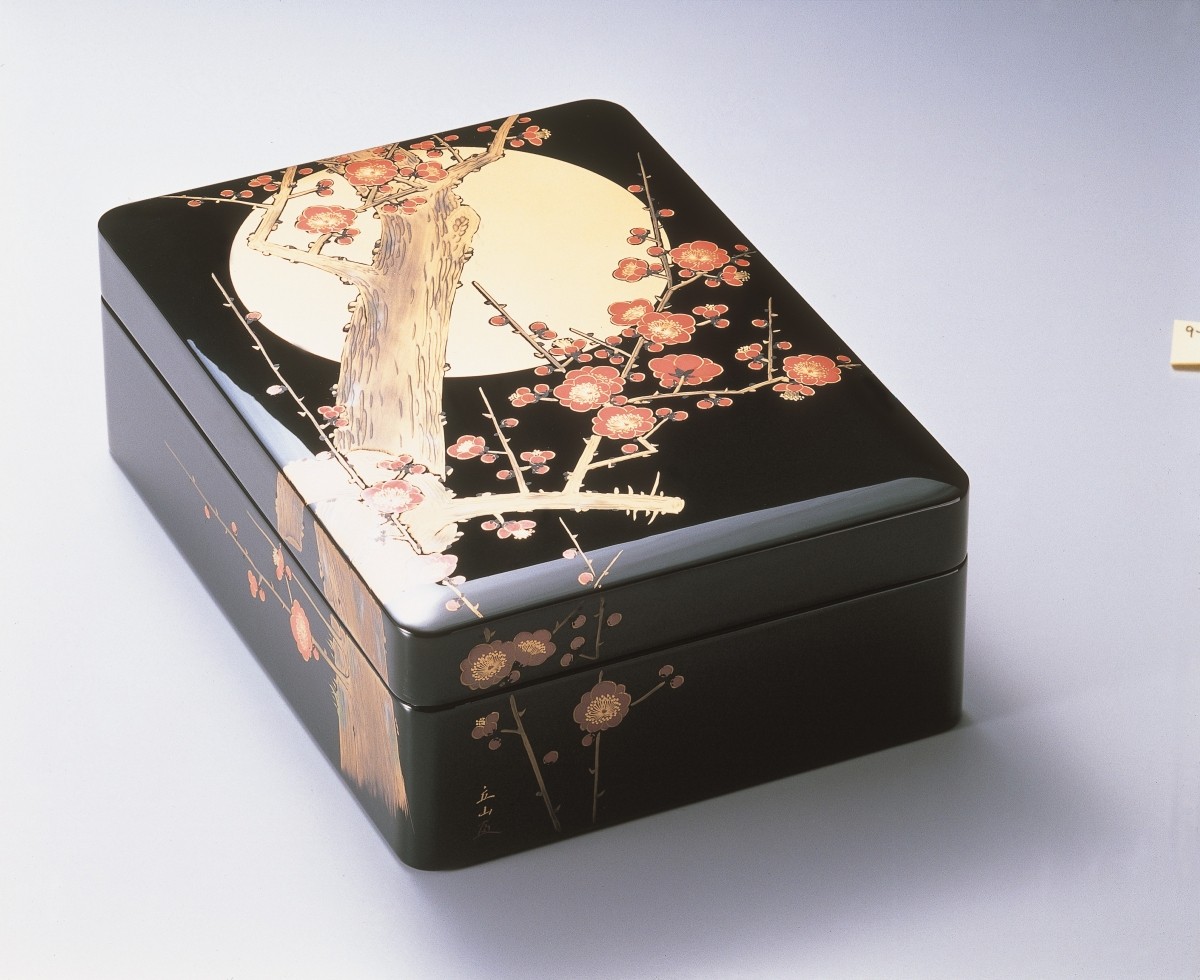

Lacquerware decoration techniques can be broadly categorized into four types: maki-e (sprinkled designs), haku-e (foil designs), chinkin (gold inlay), and raden (mother-of-pearl inlay). These methods use materials like gold and silver powders, gold and silver leaf, colored lacquer, and shell inlays to create intricate patterns. Many lacquerware items feature elaborate, artistic designs that are both vibrant and highly refined.

The History of Japanese Lacquerware

Lacquerware has been used in Japan since the Jomon period. Some of the oldest examples in the world include fragments of lacquered combs dating back approximately 7,500 to 7,200 years. By the 8th century, various techniques had emerged, and between the late 8th and 12th centuries, decorative methods such as maki-e and raden evolved, with luxurious designs favored by the aristocracy.

From the late 12th century onward, lacquerware became popular among samurai and monks for everyday use. In the 16th century, lacquerware was exported to Europe, with many pieces featuring maki-e and raden techniques. During the Edo period (17th–19th centuries), lacquerware became widely used by the common people and underwent significant development. Today, Japanese lacquerware is highly valued by collectors worldwide for its artistic and historical significance.

Production Areas of Lacquerware as Traditional Crafts

The production regions designated as traditional crafts for lacquerware are spread across Japan, from the northern region of Aomori Prefecture with its Tsuji lacquer and Iwate Prefecture's Joboji lacquer, to the southern island of Okinawa with its Ryukyu lacquerware. There are over 20 such regions across Japan.

Among these, Ishikawa Prefecture stands out. Since the Edo period, lacquerware production in this area has been nurtured under the patronage of local feudal lords. As a result, Ishikawa is home to three famous production regions, giving rise to the saying: “Yamanaka for wood bases, Wajima for lacquering, and Kanazawa for maki-e.” Each region boasts unique lacquerware characteristics.

Japan’s Three Great Lacquerware Styles and Four Great Lacquerware Styles

The "Three Great Lacquerware Styles" of Japan include Aizu-nuri, Kishu lacquerware, and the combined category of Wajima-nuri and Yamanaka-nuri, both from Ishikawa Prefecture. Despite sharing a place in the list, Wajima-nuri and Yamanaka-nuri have distinct features. When Echizen lacquerware is added to the mix, these are collectively known as the "Four Great Lacquerware Styles of Japan."

Aizu Lacquerware (Fukushima)

Aizu lacquerware is produced in the Aizu region of Fukushima Prefecture. It is renowned for its beautiful coatings and decorative techniques like maki-e. This lacquerware is highly durable, resistant to water absorption, heat, acid, and alkalis. Various advanced finishing methods are employed, with the most iconic being hana-nuri, where oil is added to create a glossy finish.

For decoration, Aizu lacquerware often uses the keshifun-maki-e technique, which involves drawing designs with lacquer-infused brushes and applying ultra-fine gold powder (keshifun) using cotton during the drying process. Typical motifs like pine, bamboo, plum blossoms, and ritual arrows, known as "Aizu motifs," are celebrated for their auspicious symbolism and vivid hues created with blue and yellow lacquer.

🌸【Yahoo!Shopping] Buy Aizu Lacquerware

Kishu Lacquerware (Wakayama)

Kishu lacquerware, also called Kuroe-nuri, has been crafted in the Kuroe district of Kainan City, Wakayama Prefecture, since around the 1400s. It became widely loved during the Edo period for its practical and durable design. Unlike most lacquerware, Kishu lacquerware uses persimmon tannin (kakishibu) and animal glue (nikawa) in the undercoating, conserving valuable lacquer while ensuring durability.

It is believed that Kishu lacquerware originated from Negoro-nuri, a style of everyday lacquerware made by monks at Negoro-ji Temple. The original Negoro-nuri often had uneven coatings, where the red lacquer would peel away to reveal the black undercoat. This accidental effect gained popularity, and artisans began intentionally creating products with peeled red lacquer designs. During the Meiji era, techniques like maki-e and chinkin were introduced, allowing Kishu lacquerware to continuously evolve over time.

🌸【Yahoo!Shopping] Buy Kishu Lacquerware

Yamanaka Lacquerware (Ishikawa)

Also known as Yamanaka-nuri, this lacquerware is produced in the Yamanaka Onsen area of Kaga City, Ishikawa Prefecture. The region has a long history of wood base production, boasting the highest output of turned wood bases (hikimono-kiji) (*1) in Japan. One defining characteristic of Yamanaka lacquerware is its use of vertical wood cutting, which follows the grain of the wood to prevent warping and ensure durability.

Another hallmark feature is kashoku-biki, the technique of creating ultra-fine grooves on the surface of the wood. Introduced during the mid-Edo period, tea utensils with elegant maki-e decorations from Yamanaka lacquerware are highly esteemed.

*1: Hikimono-kiji refers to the technique of turning wood on a lathe and shaping or decorating it with blades.

🌸【Yahoo!Shopping] Buy Yamanaka Lacquerware

Wajima Lacquerware (Ishikawa)

Wajima lacquerware is produced in Wajima City, Ishikawa Prefecture. It is celebrated for its meticulously layered lacquer coatings, beautiful maki-e and chinkin decorations, and exceptional durability. These qualities are maintained through strict standards that define what qualifies as Wajima lacquerware.

One such standard involves the use of Wajima-jinoko, a powdered material made from burnt diatomaceous earth sourced from the Noto Peninsula. Other criteria include reinforcing weak parts of the wood base with cloth (hemp or silk gauze), using natural lacquer, and specifying the types of wood used for the base.

Thanks to these rigorous standards, Wajima lacquerware combines beauty, a gentle touch, antibacterial properties, insulation, and more. Its robust construction allows it to be repaired when scratched or worn, enabling long-term use. Truly, Wajima lacquerware is a vessel that can grow with its owner.autiful, but also has a gentle touch, mouthfeel, antibacterial and bactericidal properties, and heat insulation. In addition, because it is robust, even if it is scratched or peeled off, it can be repaired and continued to be used for a long time. It is truly a vessel to be nurtured.

🌸【Yahoo!Shopping] Buy Wajima Lacquerware

Echizen Lacquerware (Fukui)

Echizen lacquerware is crafted in and around Sabae City, Fukui Prefecture. Known for its elegant luster, rich and deep hues, and lightweight durability, it has been a hallmark of refined craftsmanship. Decorative techniques such as chinkin and maki-e were introduced in the late Edo period, leading to the production of beautifully adorned lacquerware. Before the Meiji era, the focus was on roundware, like bowls, but production expanded to include square items such as tiered boxes and trays. Today, a wide variety of lacquerware is made in this region.

🌸【Yahoo!Shopping] Buy Echizen Lacquerware

How to Use and Care for Lacquerware

Using Lacquerware

Lacquerware is resistant to acids, alkalis, and alcohol, making it suitable for serving a variety of dishes. However, it is not ideal for long-term food storage. Additionally, exposure to high temperatures, such as in microwaves, ovens, or boiling water, may cause the lacquer to peel. For soups and other warm dishes, it is best to keep the temperature between 70–80°C to ensure longevity.

When using cutlery with lacquerware, avoid metal utensils as they may scratch the surface.

Caring for Lacquerware

If a new lacquerware piece has an odor, wiping it with a soft cloth soaked in diluted vinegar and rinsing with warm water can help. For regular cleaning, use a mild dish detergent and a soft sponge to gently wash the surface. Rinse with lukewarm water and dry immediately with a soft cloth to remove any water droplets. Regularly polishing with a cloth not only prevents water spots but also enhances the lacquerware's surface, gradually increasing its shine. Natural drying is less recommended.

When storing lacquerware, avoid stacking it with ceramic or glass dishes, as these can cause scratches. If stacking lacquerware, consider placing a soft cloth or tissue between items for added protection.

Comments